Primary care shortage affects 44% of Virginia’s neighborhoods and almost 3.8 million residents, new VCU study finds

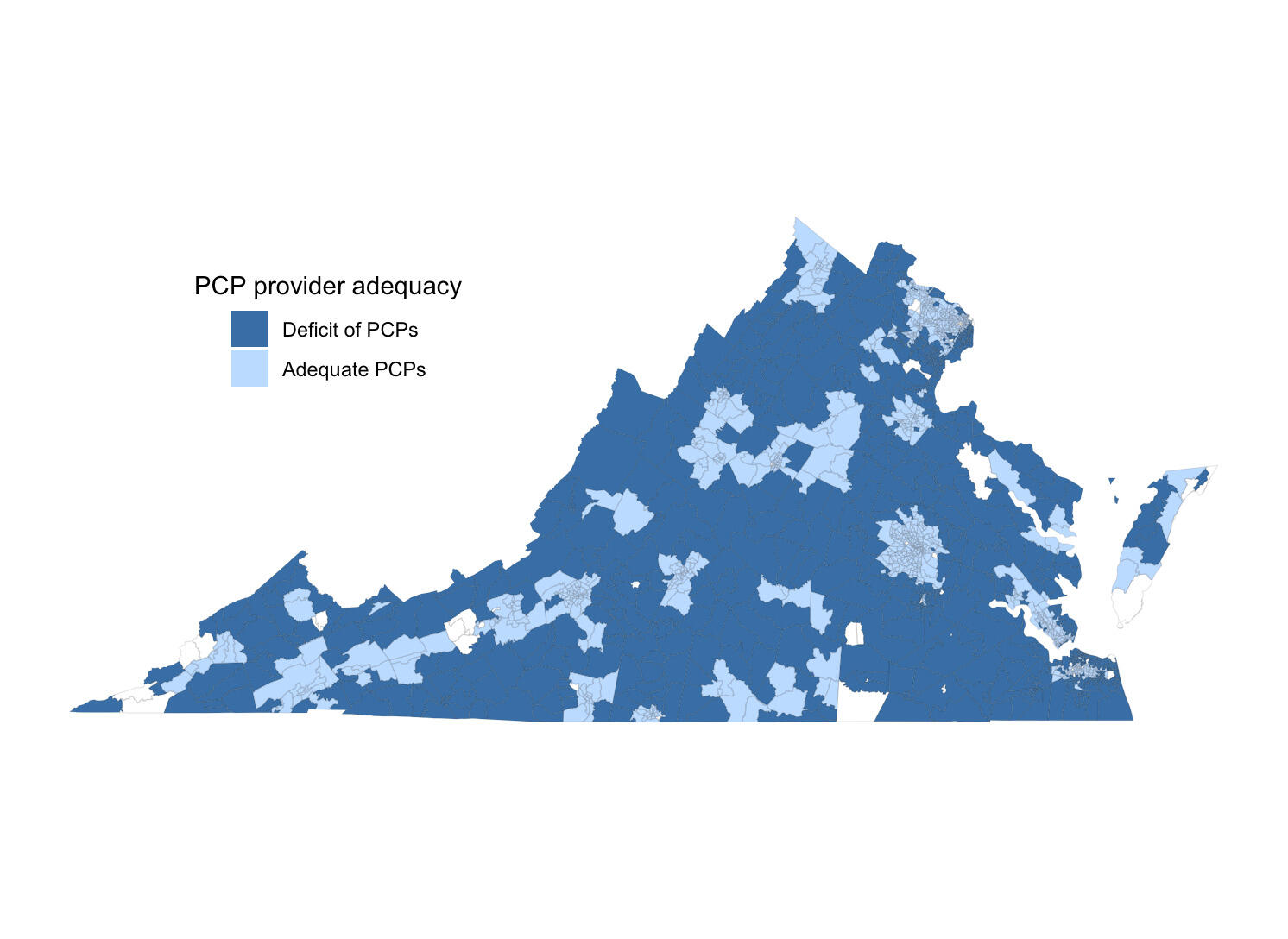

Nearly half of Virginia’s neighborhoods don’t have enough nearby primary care physicians for their residents, with rural communities being hit hardest by workforce shortages, according to a new study led by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Using anonymized health care claims data, the research team found that 44% of census tracts in the state lacked adequate access to primary care services, affecting nearly 3.8 million Virginians. The findings, published in the Annals of Family Medicine, could help inform workforce interventions in targeting neighborhoods most in need of expanded primary care access.

The researchers leading this study were supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health.

“Primary care physicians are the foundation of any health care system, with the ability to provide care across the spectrum of people’s lives,” said Hannah Shadowen, Ph.D., an M.D.-Ph.D. student at VCU’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health and lead author of the new study. “Not only do they help treat acute medical problems, they also play an important role in helping patients manage chronic health issues like diabetes and hypertension.”

Yet health care workforce shortages have worsened in the United States, and the need for primary care physicians is expected to keep growing. According to estimates from the Association of American Medical Colleges, by 2032 the United States will be short by more than 55,000 primary care physicians in meeting the health care needs of Americans.

Residents in areas with limited health care options often need to travel farther for medical appointments, and they consequently are less likely to utilize primary care services. This is a serious public health concern, as inadequate access to primary care results in more hospitalizations and emergency department visits, shorter lifespans and greater health inequities for communities.

“In order to develop interventions that effectively address primary care shortages, we need to better understand which communities are facing the biggest barriers to access,” said Alex Krist, M.D., a professor in the VCU School of Medicine’s Department of Family Medicine and Population Health and one of the study’s co-authors.

By evaluating patient claims data collected in 2019 through the Virginia All-Payer Claims Database, Krist, Shadowen and their colleagues determined the number of physicians actively providing primary care in Virginia, the locations of their practices and the number of patients seen by each physician. The researchers also included obstetrician-gynecologists, internal medicine physicians and pediatricians seen by patients for wellness visits.

“While some studies estimate how many patients a provider should be able to see annually, this data really speaks to the actual capacity of each provider and the type of care they can give to the community,” Shadowen said. “Rather than giving a prediction on health care shortages, this data provides a realistic depiction of the primary care workforce in Virginia and where the shortages are felt most prominently.”

The research team then calculated the total patient capacity of all primary care physicians within a 30-minute drive of each census tract and compared this number with the census tract’s population size.

The research team also assessed various demographic factors to better understand whether certain community characteristics were associated with primary care access. The factors included age, insurance coverage, income level, medical needs, disability rates, education level, rurality, and racial and economic segregation.

The data showed that 4,850 physicians provided primary care services in 2019, with each seeing 1,368 patients on average. The researchers’ analysis revealed that about 44% of Virginia’s census tracts did not have adequate access to primary care physicians.

They also found that structural and geographic factors were the strongest predictors of whether a community had enough primary care physicians in Virginia. In particular, rural communities experienced significantly less primary care access compared with suburban or urban neighborhoods. On average, the primary care capacity of rural census tracts was approximately 725 patients fewer compared with that in suburban tracts.

The study authors say a number of factors may be behind this disparity. For example, the majority of primary care residencies are located in urban or suburban areas, and other research shows that physicians are more likely to practice where they receive residency training.

“These findings show that more work needs to be done to increase Virginia’s rural primary care workforce,” Shadowen said. ”For example, expanding residency programs in rural settings or establishing incentive programs like loan repayment benefits could potentially help with closing these gaps in health care access.”

The researchers also found that census tracts with higher proportions of Black residents had greater access to primary care services than those with predominantly white residents.

“This may be due to the fact that predominantly Black neighborhoods in Virginia tend to be in urban areas, which this study has shown typically have a greater number of primary care physicians,” Shadowen said. “These trends could also be the result of local and national efforts to address the health needs of historically marginalized neighborhoods, such as Federally Qualified Health Centers and pathway programs.”

The researchers noted that having access to primary care does not always mean that these services are being utilized. Their next studies are focused on better understanding how access to care influences the likelihood of seeing a primary care physician in Virginia.

Shadowen and Krist conducted this study alongside researchers from VCU’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health: Jennifer L. Gilbert, Psy.D.; Benjamin Webel; Jong Hyung Lee, Ph.D.; Scott M. Strayer, M.D.; Jacqueline B. Britz, M.D.; Adam Funk; Roy T. Sabo, Ph.D.; and Andrew J. Barnes, Ph.D. They also collaborated with Lauryn S. Walker, Ph.D., from the Virginia Center for Health Innovation; Michael Topmiller, Ph.D., from HealthLandscape; and Andrew Mitchell, Ph.D., from the Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.

Latest Health & medicine

- Neural networks: How mentorship shaped two neurologists’ careersMore than a decade after they met, Emma Parolisi, M.D., and Kelly Gwathmey, M.D., reflect on how mentor-mentee relationships have impacted their journeys.

- Her mission: Clearing the air about the hidden danger in vapesMold? Nail polish remover? VCU forensic toxicologist Michelle Peace is unearthing what’s truly inside the unregulated products that are billed as alternatives to smoking.

- Learning at the intersection of OB-GYN and addiction treatmentThrough early clinical exposure and innovative curriculum, the OB MOTIVATE clinic prepares physicians to deliver compassionate care to pregnant and postpartum patients with substance use disorders.

- VCU researchers identify drug candidate for curbing alcohol misusePreclinical study points to potential for a drug now being tested to treat brain disorders.

- VCU School of Dentistry taps Kahler Slater and Hanbury to design new dental school buildingA new building will allow the school to welcome more patients and support continued innovation in clinical care and learning.

- Don’t cringe: Fecal waste prompts a patient-centric innovation from VCU Health nurseEmma Necessary is working with the College of Engineering and TechTransfer and Ventures to bring her bedside wedge to market.